Accomplishing Objectives

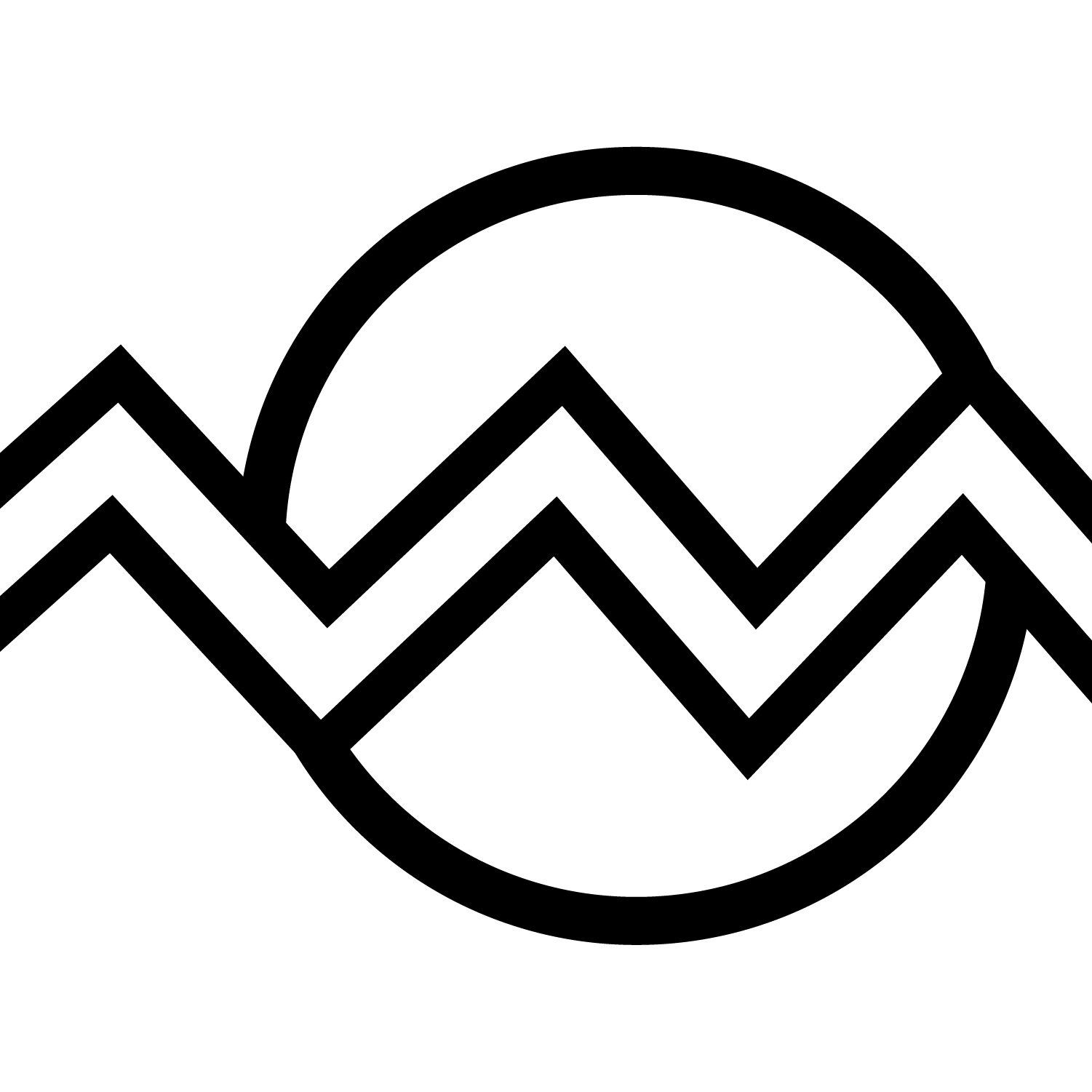

When a person has an objective, they attempt to create a path from where they are to where they want to be.

The path is rarely straight. Action creates outcomes that deviate from the intended trajectory. Each outcome becomes a new starting point, requiring a new path.

Through repeated cycles of action and correction, a person can converge on their objective — or discover that the objective lies outside the boundary of what is achievable.

The Path

An objective exists. A path is imagined from the current position to that objective.

For simple objectives, this path might be achievable in a single action. For more complex objectives, the path requires multiple steps.

Iteration

Action is taken. An outcome results. The outcome is rarely exactly on the intended path.

A new path is calculated from the actual outcome to the objective. This connects to the Taking Action cycle: Observe the outcome, Integrate it into understanding, Decide on the next action, Act.

Another action is taken. Another outcome results. Again, it deviates from the path.

The pattern continues. Each iteration provides new information about the relationship between action and outcome. Each outcome reveals something about the forces at play in the context.

Discovering Boundaries

After enough iterations, a pattern becomes visible. The outcomes are not converging on the objective. They are revealing a boundary.

The objective lies outside the boundary of what is achievable from the current position with the current resources and constraints. This is not immediately obvious from the starting point. It only becomes clear through iteration.

This connects to Doing Things: the Forces in the Context define what Forms are possible. Some objectives require Forces that do not exist or cannot be generated from the current state.

Revising Objectives

Once the boundary is discovered, a choice becomes available: continue attempting to reach the unachievable objective, or revise the objective to something within the achievable space.

Revising the objective is not failure. It is learning. The iterations revealed information about what is possible. The revised objective reflects that learning.

What happens to the original objective depends on context:

- It may be abandoned entirely

- It may be deferred until conditions change (different resources, different constraints, different context)

- It may be decomposed — part of it becomes the revised objective, other parts are set aside

The critical insight: iteration does not just correct the path. It reveals whether the objective itself is achievable.

Broader Context

Accomplishing objectives involves multiple cycles through the Taking Action loop. Each cycle generates an outcome. Each outcome provides information.

Early iterations attempt to correct the path toward a fixed objective. Later iterations may reveal that the objective itself needs revision.

This map sits at a higher level of abstraction than Taking Action. Each node in the progression shown above represents a complete Observe → Integrate → Decide → Act cycle. The map shows what happens when multiple cycles accumulate.

The speed at which a person can complete action cycles affects how quickly they discover boundaries. This connects to John Boyd's insight about tempo: faster iteration means faster learning about what is possible.

But speed alone does not guarantee success. The objective must be achievable. And achievability is not always knowable in advance. It reveals itself through action.